Onboarding of new board members is often treated as an administrative and logistical exercise: ensuring documents are reviewed, introductions are completed and making sure the new member feels comfortable as quickly as possible. When this approach does not deliver the preferred outcomes, this is not due to weak execution. The cause is the assumption on which the approach is based: it assumes that board effectiveness mainly depends on how much information a new member receives. That assumption is incorrect.

Research on board effectiveness shows that new board members rarely perform poorly because they lack expertise. More often, they perform poorly because they receive relevant information too late, lack clarity about their role or are not accepted as full participants in board discussions yet. Board productivity is therefore not an individual learning issue. It is a governance issue.

More information does not solve the problem if context is missing

Governance research shows a clear relationship between board effectiveness and access to information. When information is fragmented, selectively presented or disconnected from decision making, oversight quality declines. This effect applies to all board members, but it affects new members more strongly.

Wealth & Digital Trust Services

Protect, grow, and earn – with licensed wealth and digital trust solutions.

Wealth today extends beyond savings, shares, and property. Digital assets such as cryptocurrency and tokenized investments are increasingly part of modern portfolios.

Our Wealth & Digital Trust Services unite all your assets into a single, secure, and fully licensed trust structure designed to protect, manage, and grow your capital.

Read more →

Boards in such cases often respond by expanding onboarding materials. They provide more documents, longer presentations and larger board packs. This response does not solve the issue. Information without context increases dependence on existing interpretations and power relations. New board members do not need more data. They need clarity on how information is used. They need to know which indicators influence decisions, where risks arise and which reports support decisions rather than serve formal reporting purposes. Without this clarity, information remains ineffective.

Silence results from uncertainty, not from lack of competence

A common assumption is that new board members remain silent because they are still learning the business. Research on board behavior does not support this view. New members often hesitate because they do not know when to speak, how direct they can be or how their comments will be received.

Every board operates with implicit rules. These rules determine who speaks first, how disagreement is expressed and what happens when established views are challenged. New board members do not know these rules yet. Each intervention therefore carries reputational risk. Silence is a rational response in such situations. Onboarding that ignores these dynamics reinforces restraint instead of engagement.

Board onboarding is not an HR activity

Many organizations treat board onboarding as part of their HR processes. This approach is structurally flawed. Boards do not function like management teams. Board members are not managed hierarchically. They meet periodically and are expected to exercise independent judgment within collective decision making.

Governance literature therefore describes board onboarding as professional socialization. New board members must learn how decisions are actually made, which behavior is valued and how informal influence is exercised in practice. When onboarding is limited to documents and formal briefings, the intended learning does not take (fully) place: the expertise of the new board member(s) does not translate into effective contribution.

The chair has decisive influence

Research consistently shows that the early effectiveness of new board members depends less on onboarding programs and more on the behavior of the chair. The chair usually controls the discussion. The chair decides who is invited to speak and how contributions are treated. The chair also sets the tone for disagreement.

When the chair actively invites early input, signals that critical questions are welcome, and publicly supports new members, their engagement increases quickly. When the chair does not do this, new members tend to act cautiously. In such a situation, onboarding has limited practical effect.

Effective boards organize and manage tension rather than avoid it

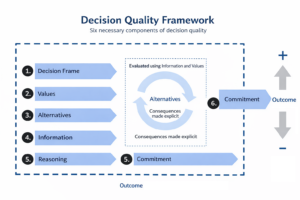

Effective boards are not defined by harmony. They are defined by their ability to organize and manage disagreement constructively. Decision quality improves when assumptions are questioned and dominant views are tested.

Onboarding that prioritizes rapid integration and minimizes tension undermines effective decision making. Effective boards provide new members a clear role early, encourage them to challenge prevailing views and protect them when they do so. This requires deliberate choices in meeting structure and evaluation. Without these choices, disagreement is suppressed and decisions lose their much needed quality.

Conclusion

Onboarding of new board members usually fails, not because it is insufficient, but because it is misunderstood. When onboarding is treated as a procedural step rather than a governance tool, board effectiveness suffers. New board members become effective when they are clearly positioned, given access to relevant context and allowed to challenge existing assumptions. Boards that fail to create these conditions accept weak(er) oversight and poor(er) decision making.

Reageer op dit bericht